History Through Coins and Banknotes: Interview with Astamur Tania

Astamur Tania, director of the National Bank Museum of Abkhazia.

Milana Zhiba | The Newspaper 'Republic of Abkhazia'

Astamur Tania, a historian and numismatist, has been the director of the National Bank Museum of Abkhazia for three years now. I had the opportunity to speak with him when the museum first opened. At that time, he gave a tour and discussed the emergence of monetary circulation, focusing on each historical period individually. Recently, we decided to talk about numismatics and its role in the life and history of a people.

Milana Zhiba: What exactly is numismatics?

Astamur Tania: Numismatics is not just the collecting of coins; it's also a significant historical discipline essential for archaeologists, historians, economists, and financiers. Coins and banknotes help us understand how trade and economic ties have developed since ancient times, what level of technology was available, and reflect the history, religion, and culture of a society. They serve as a sort of time capsule, allowing us to peer into the past and understand the interactions and connections between various civilisations. Coins offer a broader view of the world. Beyond being primarily monetary symbols, they are also works of art, propaganda, and ideology. They tell us about the weight systems used in different countries and how metal prices correlated. This underscores the importance of preserving and studying numismatic and bonistic monuments as a way to better comprehend our past and present.

Astamur, when did you become interested in collecting?

- In the third or fourth grade, I was given a 1918 1000-ruble banknote and several coins from the early 20th century. They captivated me with the possibility of physically touching the past. Reflecting on how many people had handled these items made me think about everything that had happened to these objects over the years.

An interest in numismatics significantly influenced my career choice. I initially enrolled in the history department at university, but over time, I found myself increasingly involved in civic and political activities. Fortunately, the leadership at the National Bank provided me the opportunity to return to my beloved profession, allowing me to reconnect with my passion for numismatics.

Are there many collectors in Abkhazia?

- Unfortunately, compared to the pre-war period, there are very few now; back then, the collector community was more developed. It is important for the country to have more collectors of any kind. Each collector begins to view historical heritage differently. A collector is a vital part of a modern cultural society.

Do the Concepts of 'Collector' and 'Numismatist' Differ?

- A numismatist might not necessarily be a collector; they might simply study this area of history. It is a supporting historical discipline. An archaeologist cannot work without knowledge of numismatics. For example, the Lykhny Palace (Palace of Princes Shervashidze-Chachba -ed) was dated to the 11th century, thanks in part to the discovery in the 1980s of a large hoard primarily comprising silver coins of the Abkhaz Kingdom and gold Byzantine Histamenon. The coins of the Abkhaz Kingdom, which bear the Byzantine titles of local rulers, allow us to assess how the power and influence of this state grew in the region.

By examining all the coins found in Abkhazia and studying which coins were most common in particular periods, we can understand which regions of the world our country had the most intense trade and political connections with. For instance, from the 1st to the 3rd centuries, coins from the Roman province of Cappadocia, which administratively included the territory of Abkhazia, were widely circulated here.

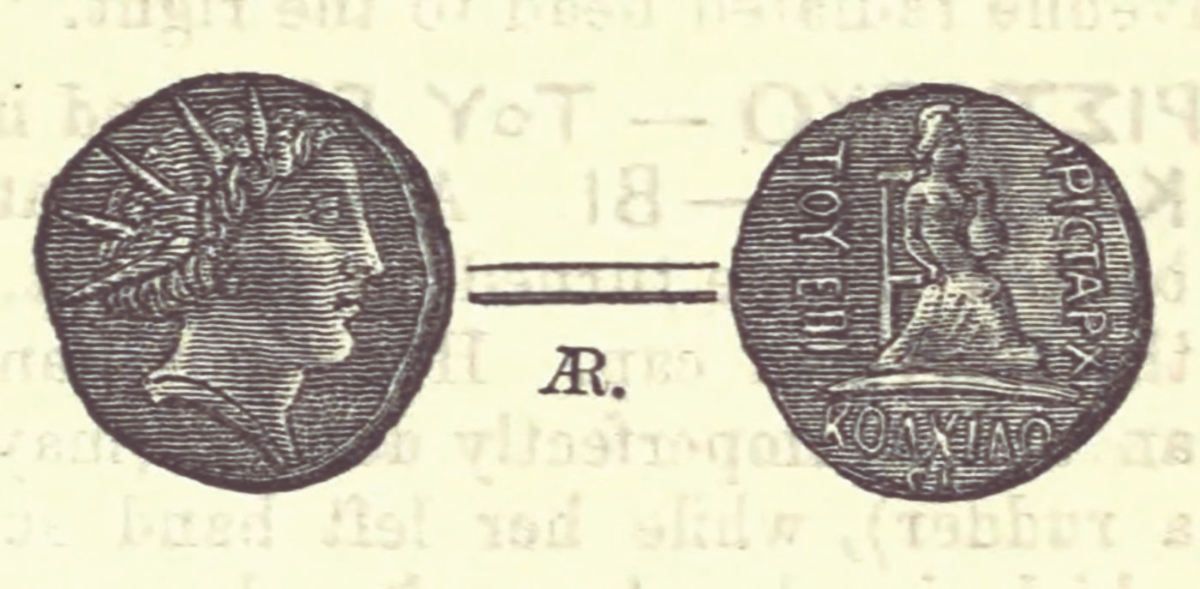

A coin known as the Drachma of Aristarchus (Aristarkhos) of Colchis, dating from 52-51 BCE.

We also encounter very interesting singular finds. Recently, a rather unremarkable-looking copper coin came to our museum, but it has a rich history—it's a 1/8 shekel from the Jewish Revolt of the 1st century CE, found accidentally in Tsebelda. It’s speculated that a Roman legionary brought it back as a souvenir. However, if more such coins are found, it might suggest more developed connections.

A coin is a very eloquent source of information; through coins, we know about many ancient rulers. From many civilisations, only ruins have survived, but coins are very well-preserved items: gold is not affected by time at all, silver is also very durable, and bronze and copper are fairly well-preserved. Therefore, coins are one of the main tools for dating archaeological sites.

When Did Banknotes Appear in Monetary Circulation? Are They Younger Than Coins?

Banknotes appeared in the 12th and 13th centuries in China. During the Mongol Yuan dynasty, they were widely used throughout the emperor’s domains, as vividly described by the famous Venetian traveler Marco Polo. As for Europe, paper money began to be introduced in the 17th century, and in Russia from 1769. In the territory of Abkhazia, paper money began circulating from the moment it became part of the Russian Empire.

Astamur, the museum consists of six departments; how long did it take to collect the exhibits?

We started assembling the collection one and a half years before the museum opened. Initially, Beslan Baratelia, the chairman of the National Bank, wanted to create an exhibition space for modern 'Apsars'. However, he later decided that it was important to create a historical exhibition from ancient times, because Abkhazia has a very rich numismatic heritage.

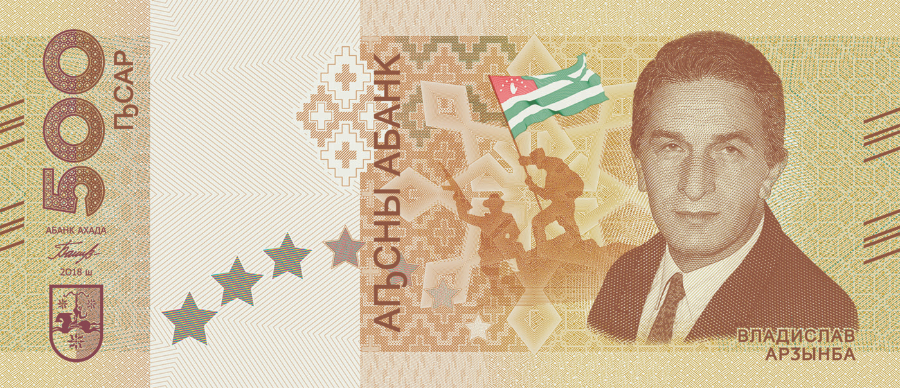

A commemorative banknote of 500 Apsars, issued in 2018.

If coins appeared in the 7th century BCE, in Colchis coins began to be minted around the turn of the 6th–5th centuries BCE, brought by Greek colonisation. Stable monetary circulation began in Abkhazia in the 4th century BCE. Greek mythology is closely intertwined with Colchis, which is reflected in the imagery on the coins.

These connections later evolved and expanded. For example, our collection includes a very rare coin from the 1st century BCE of the Colchidian king Mithridates Philopator, depicting the lotus scepter of the Egyptian goddess Isis. This indicates that the cult of this goddess, which spread widely after the campaigns of Alexander the Great, was also popular in our region. This is the story that such a small item as a coin can tell.

Astamur, we have previously discussed the museum you manage. Has the collection been enriched recently?

As I mentioned earlier, we recently acquired a coin from the Jewish Revolt. Additionally, we have acquired a local barbaric imitation of Alexander the Great's gold stater, a denarius of Mark Antony, coins from Caesarea in Cappadocia from various years, as well as coins from the Ottoman and Russian empires. The museum's collection is replenished quite frequently, some items are purchased from collectors, others are received as donations.

Since its opening, the museum has featured a coin of King Aki from the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, currently known to be the only one of its kind. The existence of this ruler was a hypothesis, albeit a controversial one, proposed by the prominent Soviet numismatist David Kapanadze in the 1950s. However, this hypothesis was confirmed thanks to the discovery of this coin in Pitsunda. The coin clearly bears a Greek inscription with the name and title of Aki.

An Aureus of Octavian, dating from the 1st century BCE (Roman coins in Abkhazia).

You have three children in your family. What are they doing, and has any of them inherited your love for collecting?

- Collecting should spark excitement, and they haven’t shown that yet. My eldest son has an interest in coins; he could get involved and understand them if he wishes, and he is currently working at a commercial bank in Abkhazia. My daughter is a student at MGIMO, and my youngest son, still a schoolboy, also collects coins from time to time, apparently under my influence.

I would advise parents to encourage their children's interest in collecting because it enhances their love for knowledge, broadens their horizons, instills a careful attitude towards the heritage of their country and global culture, and promotes the development of personal creativity and potential. It’s important to help the child choose a theme and recommend literature because collecting is not just about senselessly accumulating items, but a facet of multifaceted knowledge.

What advice would you give to beginner collectors?

I advise amateur collectors to be vigilant against forgeries. Our own Sukhum is inundated with fakes, predominantly crude copies of coins from the Russian Empire that are mass-produced in China. It's crucial to develop an eye for distinguishing these imitations to preserve the integrity of your collection.

I also emphasize that the value of a coin does not always correlate with the cost of the material it's made from; often, a copper coin can be more valuable than a gold one. It's the historical and cultural significance that often determines a coin's true worth, not just the metal it's struck from.

The National Bank Museum of Abkhazia offers lectures on numismatics, and there is a short film on the history of monetary circulation on the museum's website. A book on the same topic has been authored by Astamur Tania and Ibragim Chkadua. Visitors leave the museum with the realisation that "each coin is like a drop of eternity, carrying the imprint of the past and the potential for a glimpse into the future.

This article was published by the Newspaper 'Republic of Abkhazia' and is translated from Russian.