The Song of the Kodor Abkhazians, by Konstantin Kovács (1930)

- Culture

Konstantin Kovács’s The Songs of the Kodor Abkhazians is a seminal collection of ethnographic materials complete with musical notations, published in 1930 by the People's Commissariat for Education of Abkhazia and the Academy of the Abkhazian Language and Literature. This 72-page volume represents a significant exploration into the musical and cultural heritage of the Abkhazian people, focusing on the distinct traditions of the Kodor region. With a print run of 1,500 copies, this work serves as an essential document for understanding the intricate connections between music, folklore, and historical memory in Abkhazia.

Kovács, renowned for his pivotal work 101 Abkhazian Folk Songs (Sukhum, 1929), compiled this collection to document the cultural expressions of a people who had faced centuries of struggle, marked by conquest and resilience. His work captures the profound role that music plays in preserving collective identity, narrating historical events, and portraying social structures.

AbkhazWorld presents the first translations of The Songs of the Kodor Abkhazians, encompassing the Author’s Preface (pp. 3-5) and the initial section, Historical Songs (pp. 7-11), which covers topics such as the struggle for the independence of the Caucasus, the Russian-Turkish War (1877–78), feudalism, and revolutionary events. In time, the remaining chapters will also be translated and made available.

These translations were conducted with the aim of preserving the academic integrity and ethnographic detail of the original text, making them accessible to English-speaking researchers and enthusiasts of Abkhazian folklore.

Read more …The Song of the Kodor Abkhazians, by Konstantin Kovács (1930)

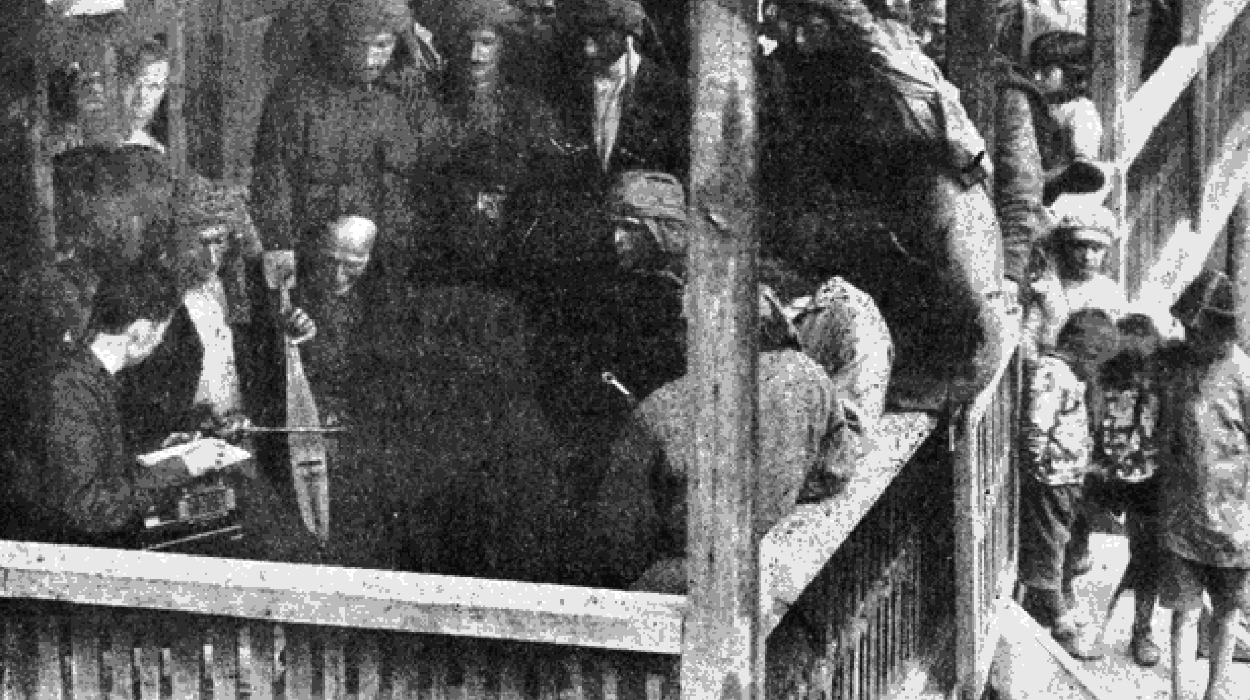

![Cult of the dead: group of mourners. Ochamchira, Abkhazia[ns]. (1927)](/aw/images/articles/Abkhazians_funeral_1927.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/articles/Abkhazians_funeral_1927.jpg?width=1250&height=700)