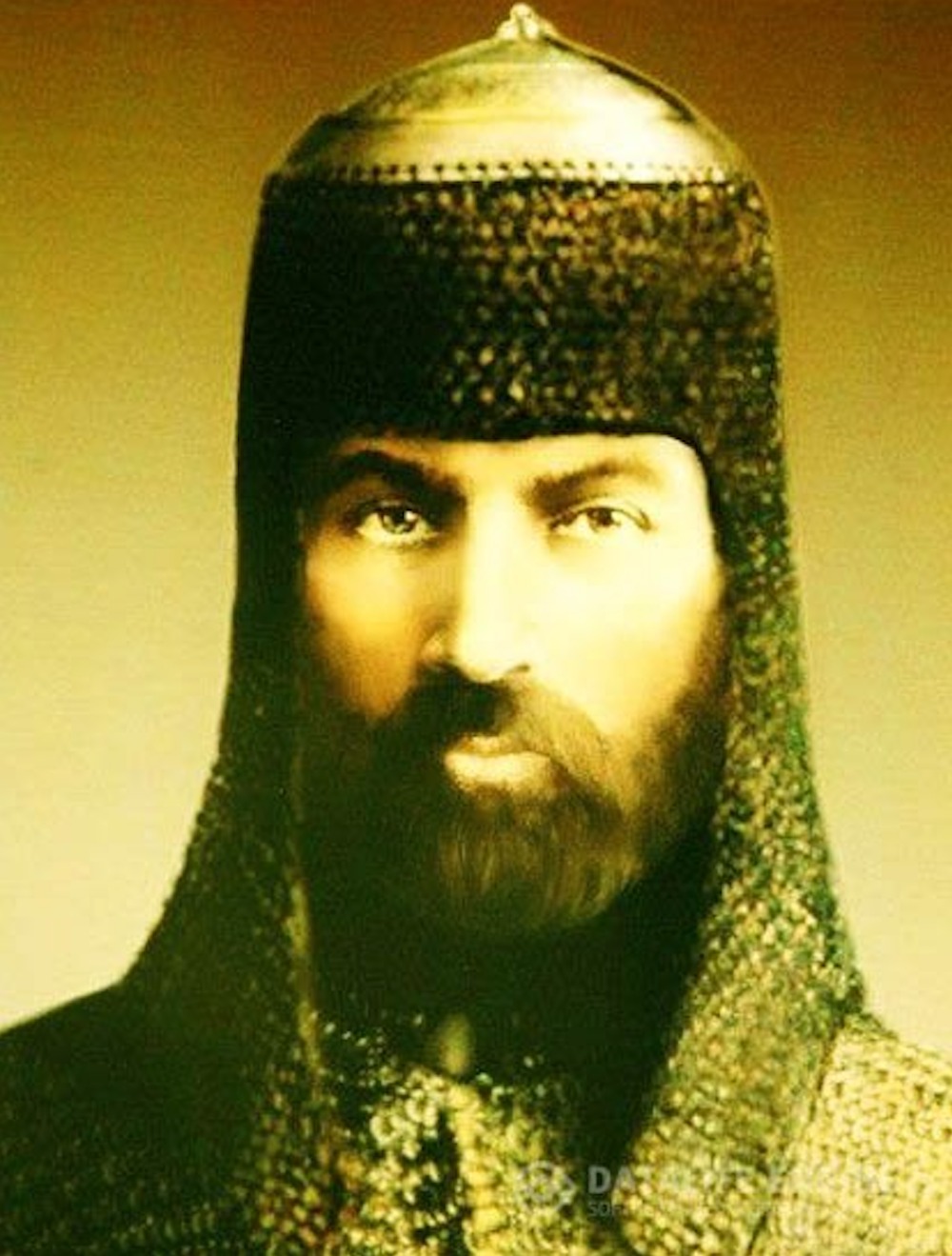

The Legendary Circassian Prince Inal, by Vitaliy Shtybin

The legendary Prince Inal is a key-figure for the Circassians, Abazinians and Abkhazians.

The legendary Prince Inal is a key-figure for the Circassians, Abazinians and Abkhazians, a unifier of lands who founded the main princely generic branches of the plain Circassians. Let's see how legendary the figure of Prince Inal is and who he really was.

Origin

Inal is considered the ancestor of the Kabardian, Besleney, Temirgoy, Khatukay and part of the Khegayk Circassian tribal princely families. He is mentioned in the second part of “The Tale of the Circassian Princes”, the narrative of which opens with the story of the military leader Kes, then names two of his successors and then tells of his great-grandson (according to other versions: grandson or son), who was named Inal. The son of Khuryfelya, Inal, as the illustrious “pshy”-prince, credited with the tradition of ordering the philosophical and ethical rules of Adyghe-Khabze [Circassian Etiquette]. Tradition does not doubt the historical reality of Inal – he is portrayed as an ideal ruler, who long and wisely ruled the Circassian tribes.

Apparently, as the ruler of Circassia, Inal made himself felt in the last third of the 14th century, during the period of great turmoil under the Golden Horde, caused by the consequences of a global plague-pandemic. Not only Genghisids, but also the temniks (war-chiefs) Mamai and Haji Cherkess entered the political scene during the Horde in those years. Inal served as a collector of disparate Circassian possessions and lands, former tributaries of the Horde, similar to that performed by Ivan Kalita in Russia.

A letter of 1753 addressed to the Russian Empress Elizabeth Petrovna by the three Kabardian princes leads to the time designated for the formation of Inal’s power. It combines the time of Prince Inal and Khan Dzhanibek. The letter says: "At the time ... Inal was in the Crimea, Janibek Khan was the khan, and since then Abazin(ian)s are in our possession". Historians and naturalists Dubois de Montpereux and Leonid Liulier in the first half of the 19th century believed that Prince Inal reigned in the early 15th century.

We can assume that the reign of the ancestor of the Circassian princely families falls within the last third of the 14th and early 15th centuries, several decades before the Ottoman Empire captured the northern coast of the Black Sea during the era of Genoese trading-posts. In the 19th century, the historian and compiler of folklore, Sultan Khan-Girey, connected the Shanjir settlement on the Kuban River near the modern city of Slavyansk-on-Kuban with Inal. It is believed that this powerful Temirgoy fortification served to deter the attacks of nomads and the Mamluks, professional warriors, who returned from Egypt, could have had a hand in it.

The legend of the Egyptian origin of Inal was adopted in Moscow in the middle of the 16th century. In 1798, at the next confirmation of the rights and dignities of the Cherkassky princes in Russia, the Cherkassky coat of arms was approved, which depicts a turban with a feather, worn on a golden crown in honour of an Egyptian legend. This was done to strengthen the noble position in the élite system of the Russian Empire. Among the Mamluk sultans of Egypt, there really was Sultan al-Ashraf Saif ad-din Inal from the Circassian clan Karmoko, who was a Circassian by the origin and who commanded the Egyptian navy. He ruled from 1453 and died in February 1461 at the age of 80. According to reports, this Inal was buried in Cairo, and so he could not have established a clan of Circassian princes in the Caucasus. He is probably just the namesake of the Circassian prince, especially since the name Inal has always been common in the Circassian milieu. This name has its roots in the Turkic language from the word “Leader,” just as the popular name Asker comes from the Turkish word for “Soldier”. Nevertheless, the version is still very popular, since it was developed by Shora Nogmov (Nogma), who suggested that Inal was a descendant of the Arab Khan of Egypt, whom he considered a relative of the Circassian Mamluks. True, in the descriptions of Shora Nogma there are very serious inconsistencies (e.g. give or take 60 years), which speaks more about artistic imagination, designed once again to strengthen the connection between the Circassians and Arabs.

Another version was voiced by the Circassian historian Samir Khotko in the book “Circassia”. He suggested that there were two different Inals. One lived in the 13th century, was a pupil of the Golden Horde khan Uzbek and the founder of the Temirgoy clan of the Bolotokovs. And the second Inal Kabardinsky appeared later, in the second half of the 15th century, with whom the story described in the “Tale of the Circassian Princes” is connected.

Another mistake is connected to the name of Inal. In Kabardian legends it is called Inal-One-Eyed (Nef). But in the West Circassian language it is sometimes customary to read a name through the distorted Nehu, which means "Fair-faced." Such a translation is impossible, since the legends of Inal were originally reproduced precisely in the Kabardian or East Circassian dialect.

The Statue of Prince Inal the Great in Abkhazia: A potent symbol of the timeless unity of the Circassians and Abkhazians.

Activity

Numerous and widely known traditions and documents paint a detailed picture of the unification of the Circassian and Abazinian principalities and possessions under the authority of Inal. He united the disparate Circassian tribes and established the authority of Inal’s princely house in the vast expanses of the North and Southwest Caucasia, starting from the Taman Peninsula River, to the River Bzyp, which flows into the Black Sea and further to the Caspian steppes adjacent to the mouth of the River Terek. Inal had a great influence on the Circassian inhabitants of Crimea. Since the days of his legendary great-grandfather, the Arab Khan, the Circassians lived in the southern part of the peninsula in the Cherkes Tuz Valley (Circassian Valley), where the River Kabarda flowed and the Cherkess-Kermen fortress was located. Inal himself initially began to rule in the area south of the Kiziltash estuary in Taman, where at that time mainly Khegayks and Zhane Circassian tribes lived.

According to Shora Nogma, the Circassian and Abkhaz nobles tried to prevent the rise of Inal, but in the decisive battle he managed to defeat the combined army of thirty large feudal lords. He ordered ten of them executed, the rest forced to swear allegiance. Moreover, it is known that the battles took place somewhere in the area of the River Mzymta, and Inal used loyal Khegayks to suppress the uprising. Given this fact, it can be assumed that he himself was from the Khegayk tribe. The aggressive and unifying movement under the banners of Inal sprang up from west to east. In the end, the people of Circassia universally recognised Inal as their great and supreme prince. To govern the country and resolve disputes, Inal set 40 judges over the people, according to the number of individual principalities and possessions. Some clans, apparently, until the 19th century kept some relics associated with Inal. Historian Pototsky mentions a golden cross, and the sanctuary (anykha) that carries his name on the river. Pskhu, on the upper Bzyp, until recently (according to Inal-Ipa) was considered to be Abkhazian [the settlement of Pskhu is still part of Abkhazia – ed.].

At the same time, Samir Khotko believes that Inal accompanied the long migration of Kabardians from Taman to Kabarda. He died in the middle of this process, when the future Kabardians, named after one of his military leaders, lived in the upper reaches of the Laba and Zelenchuk rivers. Later, Besleney Circassians settled there, and the tomb of Inal in the form of a huge mound on the upper Zelenchuk in the mid-19th century would be used for trade-fairs and meetings.

Inal-Kuba, grave of Inal in Pskhu. It's one of the Seven Shrines of the Abkhaz in Abkhazia.

According to another version, a few decades after the death of Inal, with the advent of Turkey and the Crimean Khanate in the North Caucasus, his descendants began their relocation to Kabarda. The two grandsons of Inal, Kabarti-bek Tausultan (Kabard) and Kaituko, who at the same time gave their clan name to the region and divided Kabarda into Major and Minor, headed the migration from Anapa to Pyatigorsk. The ethnographer Leonid Lavrov also wrote that "... the Kabardinians first lived somewhere in the vicinity of the Shapsugs, that is, in the lower Kuban. Folk-legends about the resettlement of the Kabardians, although they differ in details, unanimously consider the Taman Peninsula and the Black Sea coast to be the ancient abode of the ancestors of Kabardians". The latter opinion, confirmed by the results of archaeological research, as well as archival sources, today seems to be the most plausible. The Kabardians left the Crimea, returned to the old dwellings in the Kuban and settled on the island that surrounds the Black Sea, part of the Sea of Azov and two branches of the River Kuban. While everything was calm, they called the country of Kizil-Tash ("Red Pocket"). And now there is the Kiziltash estuary near Anapa. However, later they were forced to first move to the River Belaya, and then further, ultimately to Kabarda under the onslaught of the Turks and Krymchaks, with whom they had constant battles.

According to legend, Inal, during his life, divided all his possessions into four and handed them over to his sons, who became the ancestors of the current Circassian tribes: Temirgoys descended from Temryuk, Besleneys came from Beslan, Kabardians came from Kabart — only the Shapsugs did not accept the name of the fourth son, Zanoko. This clan-name was established among the Zhane and Khegayks. Inal himself remained living among the Temirgoys, but Temryuk, whom Circassian songs call "the man of the iron heart", soon rebelled against his father, deprived him of power and declared himself Prince of princes. Maybe he was that Temryk, Turkish ally, who rescued a future Turkish sultan with the result that the Turkish fortress Temryuk, built-in 1515 on the Taman peninsula, was named after him.

The brothers did not recognise his supremacy, but Inal, whom the people regarded as a saint, brought about a reconciliation, bequeathing when dying instruction to his sons to honour the Temirgoy prince as "the prince of princes", in memory of the fact that he, while dominating all the Circassians, stayed among the Temirgoy people. According to another legend, after a successful war with the Genoese, Inal summoned the four sons from his first wife and announced: "From now on, all the lands that are controlled by the Tambiyevs, I call Kabardey. The name of a person like Kabard cannot be forgotten." After the death of the father, the sons divided the Circassian land among themselves. The oldest, Tabulda, acquired lands east of the River Psyzh (Kuban), which included territory that was called by Inal "Kabarda". The second son Beslan got the land between Psyzh and Laba, the third Chemrug that from Laba to Pshish, and the youngest son Zhane received the land further to the sea. Since then, those lands have been called Beslan, Kemrug and Janei. But Tabulda did not dare to replace the name "Kabarda" assigned by his father. According to Nogma, Inal was generously gifted by nature, having all the qualities of a great and virtuous people. Under his firm and prudent control, unrest between the Circassians ceased. Wise decrees strengthened the emerging serenity and maintained peace and prosperity for half a century.

According to Khan-Girey, he was considered “a supernatural person, endowed with holiness, and people would reverently call for help from “Inal, God of happiness” in the firm belief that the name of a great ancestor could contribute to the success of any undertaking. Various places carrying the name of Inal were considered sacred: Inal’s spring near Anapa, the River Inal, flowing into the Kuban to the right below the aul [village] of Humara, Mount Inal between the rivers Baksan and Malka in their upper reaches, Inal Bay on the Black Sea in the vicinity of Gelendzhik, Inal Valley in the upper River Shah, etc.

Idar of Kabardia (1502-1571), the great-grandson of Prince Inal.

The sons, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Inal divided among themselves the entire territory of Circassia. The power of each of these principalities constantly increased, as did the ambitions of each specific prince, creating the basis for internecine clashes, splitting the country into a large number of small possessions, politically and economically poorly connected with each other. This made it possible to destroy in many ways the very fragile unity of the country that had been achieved by Inal. The principalities were formed and exalted, asserting subordination to their influence across Circassia. These include Jane, whose territory included part of the coastal strip of the Sea of Azov between the mouths of the Kuban and Don. In the first half of the 15th century, a successful struggle with the Crimean Tatars and a sharp increase in the size of the territory they occupied placed Jane among the most powerful and influential principalities of Circassia. According to Khan-Girey, even the Kabardians "more than once experienced the greed, overweening pride and marauding raids of the Janeans". Regarding the unity of interests and centralisation of power, Circassia in the second half of the 15th century was not vastly different from its state in the 10th century, known from the descriptions of the Arab geographer al-Masoudi. Nevertheless, part of the Kabardian nobility managed to conclude an alliance with Russia. The Kabardian prince from the Tal'ostany region, Temryuk (Kemirgoko) Idarov, was considered the great-grandson of Prince Inal and a subject of Russia. In the 16th century, he secured this union through a daughter, Kucheni (Guaschenei), who became the Russian Tsarina Maria Temryukovna, the third wife of the Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible.

Vitaliy Shtybin

Undergraduate historian and blogger. His YouTube Channel “Stieben On Air - Circassian Notes”, dedicated to the history of Circassian people, their culture and languages.

First published on CircassianWorld.com