Learning from the past: What Europe should learn from the mistakes made in Artsakh, by Sascha Düerkop

Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh Burn Down Homes Ahead of Azerbaijan Handover.

The Second Artsakh War is over. About 6,000 human beings lost their precious lives to get out of one stalemate and straight into the next one. Russian troops have been deployed to ensure that the new uncertainty is not challenged militarily again, at least for the five years to come. The European Union, which often claims to be the second relevant superpower in the Caucasus, watched the signing of the peace-deal as it did the entire six-week-long war – concerned and inactive. As a European, who does strongly believe that Europe can, should, and must play the role of the protector and promoter of values like democracy and civil liberties in the world and, in particular, in its immediate neighbourhood, I was once again disillusioned. As a German, who was brought up learning that Germany’s prime role in the world is and has to be the defence of human rights and the prevention of ethnic-based hate, I was shocked by the complete reluctance of our government to step up and at least clearly condemn the ethnic hate that fuelled this war. If there is any “German value”, it is, in my opinion, the will to reflect its own past and to learn from it for a brighter future. Thus, I would like to hope that we, as Europeans, can learn from the Second Artsakh War to avoid future sufferings.

Before I detail possible lessons from this war for Europe and the international community, let me elaborate why I would like to hope, but struggle, to still believe my own core belief that lessons from the past shape our actions of today and tomorrow. Admitting, understanding and regretting the terror that Germany brought to half of the world, “never again”, rightly, became the leading principle of German politics, internally as externally. We are a nation that is extremely vigilant to anything glorifying or playing down the horrors the Nazi regime caused and, subsequently, to anything that slightly reminds us of the symbolism or the rhetoric the inhumane key figures of the system used. When Donald Trump said “you have good genes in Minnesota” or when his son Donald Jr. proposes that his father should go to “total war” to challenge the election-result, I cannot help but immediately freeze in shock. What might be seen “critical” in most of the world is crossing all lines in my country and, I believe, rightly so. Yet, coming back to Artsakh, the leading political circles of my country have had no words to spare regarding the Nazi rhetoric coming out of official Baku every day for weeks now. When President Aliyev spoke about “hunting Armenians down like dogs” or when the country officially named its drones “dog-chasers”, no German politician was bothered enough to condemn this dehumanizing language. Two Azerbaijani Ministries which run the “info-centre” Virtual Karabakh together named a whole sub-page “the Armenian Question” and, unlike in any other context, no one over here seems to be reminded of the “Jewish Question”. In other words, the Artsakh war taught me that my very own political leadership does not mind genocidal wordings and actions, if there is not enough public pressure on them to do so.

“Iti qovan” ("Dog Chaser"), Azerbaijani kamikaze drone.

Having worked with, and travelled to, most of the de facto states in the world, I naturally and primarily always ask myself what the world and, in particular, Europe, could learn from the Second Artsakh War. While my hope that anything will be learned, or that anyone would bother to try learning much from it, might be small, I am still positive enough at least loudly to think about possible lessons learnt.

Abkhazians, like South Ossetians, Somalilanders or Northern Cypriots, have surely followed the daily developments in Artsakh from a very different perspective from that of most of the world. In the end, the chilling message gained from the battlefields between Armenia and Azerbaijan is that even long-existing and relatively stable conflicts between two heavily armed factions can be solved by force — and, even worse, that war crimes will be tolerated by the world or at least remain unsanctioned, as the international community is not sufficiently interested in small specks of land that are kept in a legally grey zone for the timespan of a generation already. Finally, unrecognised and partially recognised states have witnessed that Europe doesn’t care about their fate.

+ Appeal by representatives of civil society of Abkhazia in relation to the ongoing military action in the Karabakh conflict zone

+ Abkhaz, Georgian, Ossetian peacebuilders call for an end to Nagorno-Karabakh violence

+ From Conflict to Autonomy in the Caucasus: The Soviet Union and the Making of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh

+ Mediators for Transcaucasia's Conflicts, by Elizabeth Fuller (1993)

There is a real risk that voices in Georgia, in (Greek) Cyprus or in Moldova that call for a military escalation, or “liberation-war”, will get louder as a direct result of the Artsakh war. That the Azerbaijani ambassador to Georgia met the “Chairman of the Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia”, a de facto powerless Georgian government-in-exile for Abkhazia, on the day the peace-deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan was signed, clearly was meant to send a signal to the actual Abkhazian government in Sukhum. After decades of standstill and dormant peace-talks the long unthinkable military option might make a comeback in the debates of countries that lost parts of what they see as their lands in the past. The sabre-rattling might be back, which will have its effect on each and every one of these conflicts.

Meeting between the Azerbaijan ambassador to Georgia, Faig Guliyev, and the Chairman of the "Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia", Ruslan Abashidze.

Assuming that Europe indeed will primarily defend and promote human rights and peace and that it has an interest in living in a peaceful and largely democratic neighbourhood, it thus has to avoid accepting an atmosphere whereby the heat slowly builds up elsewhere, as it did in Azerbaijan over decades. It has to get more proactive and play an actual role in solving protracted conflicts. The complexity of each and every one of these conflicts can no longer serve as an excuse not to engage in it, but rather should be a motivation to understand these conflicts better. As all outcomes of the Second Artsakh War, namely the increase of the territory in the Southern Caucasus governed by an autocratic dictatorship, an extended presence of Russian troops in the region, the destabilization of a pro-European government in Armenia and the jettisoning of the OSCE as a conflict-mediator, are in direct opposition to the interests of the EU, which simply must do better in the future, if it wants to stay relevant. It simply cannot justify any claim to stand for any values, if it is not willing to fight for them — not to its partner(s) near and far and not to its own citizens.

When I demand that the European Union engage more in these conflicts, I am not demanding that they solve them tomorrow or even sketch possible solutions that are satisfactory to everyone. All I am demanding, as a citizen of Europe, is that politicians move the solving of conflicts up their agenda, even if shots, luckily, are not fired today. The European Union must understand that peace is not just the absence of war and that it does not “promote peace”, which by its own accounts is its main goal, if it simply turns a blind eye to so-called frozen conflicts. This certainly includes Nagorno Karabakh, which seems already to be sliding off the agenda of many European politicians, days after a ceasefire with a shelf-life of just five years was signed. Europe, and Germany in particular, should remain vigilant and stand up against any racist and genocidal speeches coming out of parliament in its neighbourhood, even if it does not formally recognise the state it is aimed at.

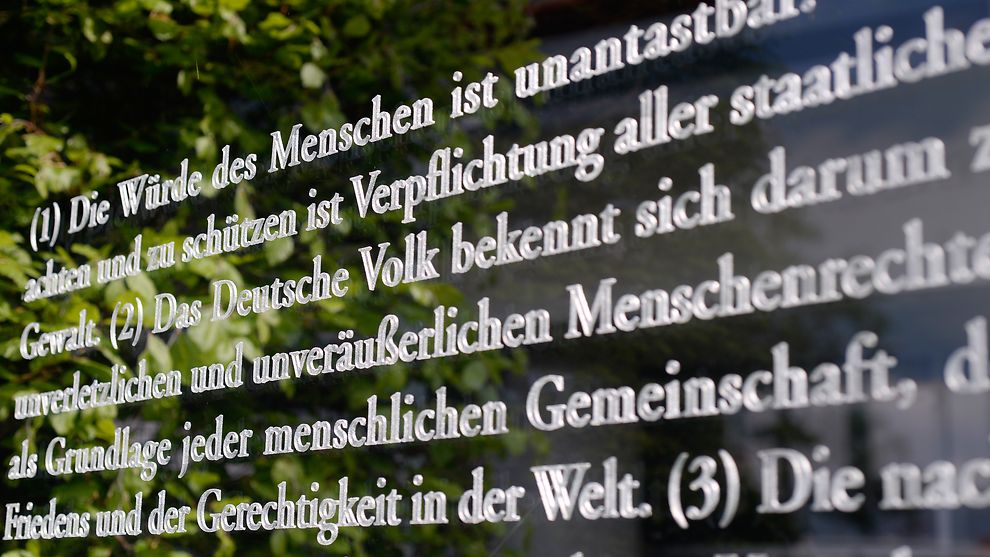

The European Union, in my opinion, should drastically change its approach to protracted conflicts. Germany’s constitution does not open with “human dignity is inviolable” by coincidence. It should allow this simple, yet wholesome, claim to shape its foreign policy and try to influence the European Union to follow suit where possible. Europe should not have the territorial integrity or the right to secede as a guiding principle, but the upholding of human rights and the promotion of peace. That, inevitably, means listening to arguments from all sides and trying to understand them. It also means working hard on drafting, creative where necessary, solutions for protracted conflicts. I am not saying this is easy, in fact it is the opposite, but I am saying it is worthwhile and to the benefit of all concerned parties.

Article 1 of the German Constitution: "The human dignity is untouchable". Installation in front of the German parliament.

Without going into detail on every single conflict and without even suggesting that I know the answer to any of the complex questions surrounding these conflicts, I want to end this commentary with a simple truth and the completely dreamt-up utopia that has formed in my mind for the Nagorno Karabakh conflict over the last few years.

The simple truth is that it is impossible to find a “fair” solution to any of the conflicts in question that satisfies all sides and is based on ethnic fault-lines. After centuries of Georgians living in South Ossetia and Abkhazia and Abkhazians and Ossetians living in Georgia, it will never be possible to define a border between these communities without suggesting ethnic cleansing. The peace-deal on Nagorno Karabakh perfectly proves just that. The Kalbajar, or Shahumyan, Rayon of Azerbaijan, or the Republic of Artsakh, used to be predominantly inhabited by Azerbaijanis before the First Artsakh War in the early 1990s. At least 40,000 Azerbaijanis were forcefully displaced from the region in 1993, which by any definition is ethnic cleansing. Ever since, Azerbaijan and the international community have demanded the return of the region to Azerbaijan to allow these Azerbaijanis to return to their homes. Now, following the Second Artsakh War, this will happen on the 15.11.2020 and it will result in nothing less than another ethnic cleansing, as now 3,000 Armenians living in the region are being forcefully evicted. The numbers might be less, but the pain is the same for each and every one of the people having to leave their home forever. These people do not only leave their house and land behind, but will most likely never again be able to visit the graves of their parents or the church in which they were baptized, given the restrictive visa regime of Azerbaijan. Just as Azerbaijanis were not able to visit the graves of their parents for the last 30 years. Wherever you want to draw a line as a border in that region, civilians will inevitably suffer and be traumatized. The only solution that does not result in atrocities is true peace – not a ceasefire with impassable borders. That is true for Artsakh, just as it is for Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Northern Cyprus, Somaliland, Kosovo, Transnistria and Western Sahara, and admitting it, in my opinion, is a first step towards opening up meaningful debates on possible solutions.

Now, I am closing this by sketching the utopia I dreamt up for Artsakh before this war. It is naturally both completely made up and unrealistic. Yet, I think it is important that all sides of a conflict, as well as think-tanks, keep coming up with crazy ideas until eventually one of them finds the acceptance of the parties involved and might eventually lead to peace and a settling of the conflict. By sharing my own dreams of a peaceful future for Artsakh, which now is more unlikely than ever, I would hope to inspire others to dream up their own for other conflicts and thus get debates started.

My Artsakh utopia is basically based on what I perceive to have been the most crucial demands of each side to the conflict and what I very personally consider justified. The Azerbaijani side always focused on their large number of Azerbaijani internally displaced people and their desire to return to the lands of their forefathers. This mainly concerns the regions outside of the former Soviet Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), where the majority of them used to live, and the city of Shushi (or Shusha). The main demand of the Artsakh Armenians was always independence from Azerbaijan, either through the unrecognised Republic of Artsakh or as part of Armenia, and keeping full authority over the NKAO. Thus, in my utopia, the NKAO would be fully independent and recognised as such, which would further provide them with the option of joining Armenia, should they and Armenia wish for such a unification. In particular, it would be recognised as independent by Azerbaijan and Turkey, who would both slowly (re-)start diplomatic relations with Armenia and Artsakh itself. In return, the surrounding regions would return to Azerbaijani control. This, in itself, would be largely in line with the Madrid Principles and not a very daring or creative solution. Yet, three crucial questions would remain open.

All three questions, in my utopia, would basically be solved by an international peace-keeping mission. These peace-keepers would not only guard and secure the border between Artsakh and Azerbaijan but would also be deployed to secure historical sites that end up on the wrong side of the border and the safety of those who maintain them. This does actually happen in Kosovo, where several Serbian monasteries are being kept safe by a stable peace-keeping mission. Finally, and most creatively, Shushi (or Shusha) would become a “demilitarized neutral city”. The international peace-keepers would police the city, ensuring that its Artsakh Armenian and its Azerbaijani citizens can live in safety. At the same time, Shushi/Shusha would serve as a “meeting point” between the two nations, as it would be made accessible from both, Azerbaijan and Artsakh, giving the people of both countries the chance to visit the city. Similar to the Ergneti market that once was the only meeting point for people from South Ossetia and Georgia, it would become much more than a neutral zone over time. It would serve as a bridge between two communities that have little understanding and lots of prejudices against each other. The sheer existence of such a meeting point would hopefully lead to a decrease of hate on both sides and help opening communication-channels between the citizens of both countries. Such steady exchange, in the end, would hopefully lead to Armenia, Azerbaijan and Artsakh being neighbours, not enemies, within a generation or two.

The military checkpoint at the "Patriarchate of Pec" in Peja, Kosovo.

This utopia cannot be easily transferred to any other conflict, such as that between Abkhazia and Georgia, as Artsakh is as unique as Abkhazia. Yet, I am sure that bright minds in Abkhazia, Georgia, Russia and in Europe could similarly sketch utopias for these conflicts, exchange their thought-experiments and confront the parties to the conflict with it to see their reactions. By bringing up proposals that won’t work for either party, or for both, the international community would still show that it really does care about the human dignity of the people living on either side of the conflict. Every utopia that is rejected will only result in a deeper understanding of the actual demands of either party and, who knows, maybe one day one utopia will actually not be rejected by the concerned parties and thereby allow peace to reign.

Sascha Düerkop

Consultant at Midfield Generals for football associations outside of FIFA, including those of de facto states.

The views expressed in this commentary are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of AbkhazWorld.