As long as the world exists: Abkhazian 'Deletion Marks' at Depo

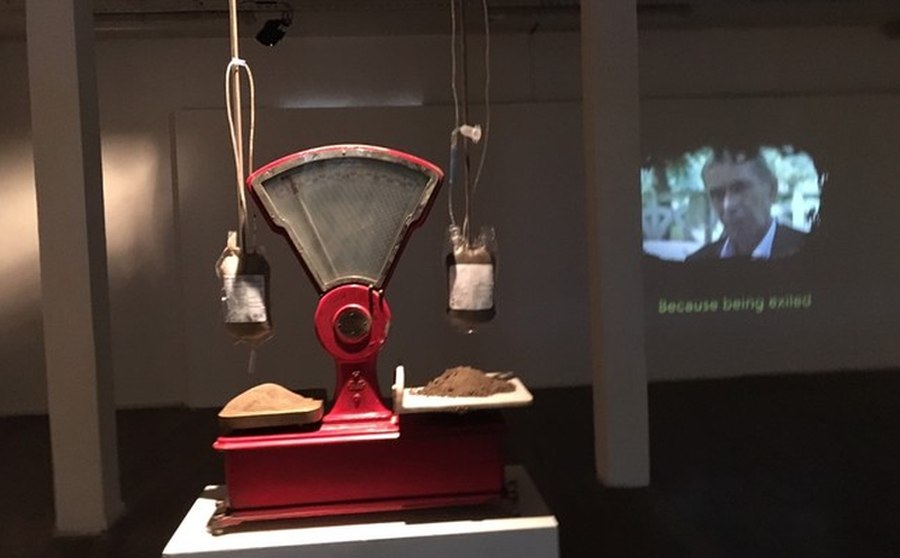

Circulatory Shock is the centerpiece at Deletion Makrs, a poetic metaphor of blood and soil in the midst of history and memory.

Daily Sabah -- An enlightened alley in Istanbul's diverse Tophane neighborhood sees locals and internationalists into the nonprofit arts and culture space Depo, where ‘Deletion Marks' exhibits the endangered Abkhazian narrative from Düzce to Sukhum, survived by a century-and-a-half of conflict, exile, and resistance.

Elisabeth Denys and Tareq Daoud first heard of Abkhazia about a year ago while living in Istanbul to produce new collaborative ideas. Denys, a social sciences researcher and audiovisual producer from France, and Daoud, an Afghani-Swiss photographer and filmmaker, received an unexpected and intriguing open call to enter the inaugural artist residency program at SKLAD Cultural Institute in the Abkhazian capital city of Sukhum on the Black Sea coast between Sochi, Russia and Batumi, Georgia. Its political and territorial autonomy as the Republic of Abkhazia is only recognized by Russia, along with a handful of smaller states.

In Turkish, the Abkhaz are known under the umbrella group of Circassian, referring to the various peoples of the Caucasus, including the Ubykh, whose entirely oral language is extinct since 1992 when its last speaker Tevfik Esenç passed away. In Abkhaz, which UNESCO lists as an endangered language, SKLAD means depot, fating it for display in the old tobacco depot of Istanbul that transformed from 2005 to 2009 into the multipurpose arts and culture complex Depo, an initiative by Anadolu Kültür in support of regional projects that protect international diversity and cultural rights.

The year 1864 is a momentous period in the history of Caucasian peoples, marking an epochal shift as Russian imperialism divided Abkhazian Muslims, exiling them to Turkey. The aftermath of 1864 is still felt by Abkhaz families in Turkey, where they have struggled for communal integrity. The traumas of deportation are embedded, as they remember the loss of the homeland after awaiting inhumane passage along the coast of the beloved Black Sea that spread them out along different Black Sea harbors, such as the province of Düzce.

While proudly maintaining ancestral Abkhazian identities, the diaspora became famously patriotic in Turkey, making great sacrifices on the embattled fronts of the Ottoman Empire. In the Republic of Abkhazia of the present, Russian aid makes up over half of the national budget, escalating since the 1992-1993 war with Georgia in return for an enviable strategic military base on the Black Sea. In the eyes of the world, formally the U.N., the Abkhazian citizenry are members of a secessionist state of Georgia as they are only issued passports through Russia according to specific visa applications. Yet, they are not granted Russian residency, and being outside of international conventions they must live without an airport and postal service, as all mail is routed exclusively through Sochi.

The after effects of economic embargo, coupled with the national security challenges that come with persisting as an unrecognized state define contemporary life in Abkhazia, a reality that Denys and Daoud learned quickly while residing in Sokhum and working at SKLAD to prepare the foundation that would become "Deletion Marks" at Depo. In many cases, seemingly simple matters like replacing a light from precious Russia goods and acquiring a glass container from a Georgian craftsman erupted into echoes of the surrounding geopolitical crises.

The centerpiece of "Deletion Marks" is titled "Circulatory Shock." It is a commercial balance scale hung with Turkish and Russian transfusion sets filled with soil extracts from Düzce and Sokhum respectively spilled out and weighed by the blaring metaphors of earth and blood lost to the ongoing condition of armed territorial disputes. "How long can one bleed?" Denys wrote on the traumas of holding fast to unity and identity despite the dismemberments of modern history. As a young artist, Denys admits that "Circulatory Shock" may seem simplistic, though when she arrived to Abkhazia she met a fellow traveler from Turkey who was overcome with a need to see her country, demonstrating the visual metaphor from lived experience.

The way to Sukhum from Istanbul is a day and half to the city of Zugdidi overland by bus, van and taxi before crossing the border on foot. Abkhaz and Russians fly to Sochi and enter with special papers, but foreigners must pass under the surveillance of the Georgian authorities who stake out the main bridge into and out of Abkhazia, as it is technically outlaw territory where the Russian military awaits on the other side. That said, travel is not necessarily prohibitive for Abkhazian people, although the land base once known as the Russian Riviera is a largely a figment of the past for vacationing families who once relished in its wine-producing subtropics and snow-capped alpine range which boasts the world's shortest river from source to mouth.

With a sharp intellect and knack for cross-cultural enterprise, Denys is as bright as she is blunt as she sparks energy into the exhibition space that she formed with Daoud over a few bouts of interactive chemistry. In Turkey, the 500,000-strong Abkhaz are so slight a minority and politically nationalist to boot as proud multigenerational veterans from the Turkish War of Independence that they hardly cause a stir.

Denys prepared the full opening of "Deletion Marks" with mosquito repellant smoke wafting about the room to recall the malaria-infested wetlands that Abkhazian exiles suffered resettling in 19th-century Turkey. In response, the celebrated academic expert Jade Cemre Erciyes said they crystallized the topics so well in the four works at the exhibition that it would take her 200 pages to summarize just one. "Compulsory Education" (2017), for example, is a multimedia composite of archaic education materials, illustrated fabrics teaching children in the 62 letters of Abkhaz alphabet with Turkish and Russian vocabularies, burned and lit through with projected videos documenting Abkhazian testimonies.

"We drew ideas on napkins in a bar. We were just talking. It was for fun, but we were selected [by SKLAD]. They received some 150 applications but all of them were more about Russian influence or Georgian war. We were the only ones offering something about Turkey," Denys says cooly through her thick northern French accent recounting how the "Deletion Marks" opening spiked public attendance to a warm reception, as followers now look forward to the discussion panel to be held 16:30 on February 24th featuring Erciyes with writer Elbruz Aksoy and an Abkhaz representative named Tayfun. "I come from journalism and production so for me I'm more didactic. I like to explain. I would love to schools come to the exhibition and be able to understand. All of the texts tell a lot. We tried something between artistic work and historical, editorial work."

Initially exhibiting in Sukhum before moving to Istanbul, the emotional power of "Deletion Marks" is buried deep in the soul of its subjects, now emergent with the sustained focus of two sensitive minds who have raised the ancestral call of Abkhazia to speak through its people despite the amnesias and displacements of its history. Although new to the culture and personally removed from the hostilities, Denys and Daoud released stimulated unheard dialogues from the Abkhazian diaspora and its strained homecoming. In the piece, "Fade In / Fade Out" a woman from Düzce plays an Abkhazian folk tune as a melancholy dirge on accordion only to hear it followed as an uproarious anthem by a national musician in Abkhazia. As an old man interviewed to pithy effect: "As long as the world exists it won't happen. Even if only ten of us were left we won't forget about Abkhazia."

Source: Daily Sabah